According to this article our societies owe a lot to crazy people when they create more than just new companies but entire new industries.

People like Thomas Edison, Matthew Boulton, Henry Ford, Howard Hughes, and into our age Steve Jobs and Elon Musk (the article was written almost two years ago so is untainted by the Twitter fight).

But if you’re going to start identifying such people, the word “crazy” must have a different definition to the commonly understood one and while the article does not try to define it their descriptions of such men are sufficient:

In the year 1800, a team of burglars broke into a factory in England to steal the workers’ payroll. The factory belonged to Matthew Boulton, an industrialist and inventor, as well as a polymath who hosted discussions with intellectuals like Benjamin Franklin, Joseph Priestley, and Erasmus Darwin.

Boulton got wind of the burglars’ plot. Like any sensible person, he decided the responsible thing to do was to assemble a posse of his friends and employees, give them guns, and lie in wait. As one biographer told the story:

…

Antics like his might be chalked up to youthful enthusiasm, except that he was 72 when he ambushed the burglars.

Hardly a sober and conservative captain of industry then. I’m embarrassed to say that I’d never heard of Boulton, though I should have because he’s the guy who partnered with James Watt and really made Watt’s steam engine take off, which was one of the keys to the Industrial Revolution. But the “crazy” continued:

After diving into the steam engine business, Boulton found that his earliest customers—copper mines—were on the verge of bankruptcy. To help keep them afloat, he invested heavily in the mines and bought large loads of copper. To make use of his new stockpiles, Boulton then personally designed a steam-powered machine to mint copper coins. When counterfeiters began copying these coins, Boulton grew dissatisfied with the police, organized his vigilantes, and hunted them down.

But the article also points out that there is a place in building these large companies and industries for people who aren’t that crazy, and it does so by contrasting what happened to the same company under the leadership of two very different men. That company is General Electric, which traces its ancestry all the way back to Thomas Edison:

Edison founded his famous Menlo Park laboratory, where he invented the incandescent light bulb, and even more importantly, the public power plant to distribute electricity to new light bulb owners. He could have had an illustrious career at the head of the Edison Electric Light Company. But instead, he turned to developing yet more industries. Edison would go on to found a dizzying array of companies…Meanwhile, he reluctantly handed off operational control of his power company…

But the man who would really make GE go was a very different type. Owen Young, born on a farm, became a lawyer, and a very good one who came to the attention of GE where he was hired as General Counsel he would rise to the rank of CEO, driving the company to take over key companies like the British-owned Marconi Company (“in order to put crucial radio infrastructure under American control“):

Under Young’s leadership, GE and RCA became enormous manufacturers of consumer goods and appliances, cementing their positions as household names. Young was also selected by statesmen for key roles on two commissions renegotiating the payment of German war reparations: the Dawes Plan and the eponymous Young Plan.

Edison would never have done that. He’d have been bored out of his mind. He constantly took huge risks with his own money and eventually he would fail in a spectacular fashion. He and Young would have clashed constantly and likely would not even have understood each other. Young was a man of The System and he knew how to navigate it and work it. But both types are necessary. The Edision’s to create and the Young’s to keep it together and build on it.

The most obvious modern comparison is Apple; saved from oblivion by the return of one of its founders, Steve Jobs, who created an almost endless list of devices that changed the computer and telecoms industry, since his death it’s been run by Tim Cooke and has continued to grow tremendously – but with almost no paradigm shifting inventions. However it’s not an exact comparison because Jobs appeared to have learnt something from being fired from his own company years earlier. A crazy creator he remained but Apple grew hugely under his leadership also, and Cooke may yet have a failure on his hands.

Musk is another modern example that is also not quite like Boulton/Edison while certainly not like Young/Cooke either. He’s moved from creating an online finance company (Paypal) to electric cars (Tesla) to rockets and spacecraft (SpaceX) to silicon chips in human heads (ugh) and high speed transport tunnels (The Boring Co.) – all while seemingly running these companies with a tight grip that has produced enormous wealth for him and his shareholders.

There’s no sign that he, Zuckerberg or Bezos want to completely hand over control of the companies they have created. Perhaps they’re not quite as crazy as their forebears, combining creativity with cold-blooded management and financial skills?

The real question is whether we can continue to produce such crazy people who push humanity along to a better future? The chart at the start of this post suggests we might not. You can’t have continuously disruptive capitalism without disruptive scientific breakthroughs and humanity seems to be approaching an asymptotic point.

This argument has been going on for years now. Peter Thiel has famously said that he had expected flying cars by now and all he got was 140 characters (a reference to early Twitter comment limits). But that second article by Robert Zimmerman makes a good point, even as it questions the Nature paper’s definition of “disruptive” – that their comment about “changes in the scientific enterprise” is the elephant in the room:

When you increasingly have big government money involved in research, following World War II, it becomes more and more difficult to buck the popular trends. Tie that to the growing blacklist culture that now destroys the career of any scientist who dares to say something even slightly different, and no one should be surprised originality is declining in scientific research. The culture will no longer tolerate it. You will tow the line, or you will be gone. Scientists are thus towing the line.

That’s one of the key points that President Eisenhower made in his farewell speech in January 1961 (quickly overshadowed three days later by Kennedy’s flashy “Pay any price, Bear any burden” effort), although Eisenhower understood the mirror effect also:

In this revolution, research has become central, it also becomes more formalized, complex, and costly. A steadily increasing share is conducted for, by, or at the direction of, the Federal government… The prospect of domination of the nation’s scholars by Federal employment, project allocation, and the power of money is ever present and is gravely to be regarded.

Yet in holding scientific discovery in respect, as we should, we must also be alert to the equal and opposite danger that public policy could itself become the captive of a scientific-technological elite.

Who is Dr Fauci?

The argument that the West in particular is running out of inventive gas is bolstered by the simple fact that lagging effects of it have passed from science and technology to companies and now to economic stagnation, as per this essay, The Age of Decay, which starts by contrasting the exciting, booming California of the post-War years to now, where it has become very much not the future that the rest of America wants:

The California culture of the 1960s now looks like a fin-de-siècle blow-off top. The promise, fulfillment, and destruction of the American dream appears distilled in the Golden State, like an epic tragedy played out against a sunny landscape where the frontier ended. Around 1970, America entered into an age of decay, and California was in the vanguard.

That writer looks across measurements not just economic but also political and social (in which he includes spiritual – I’d argue that it might be better to call it “cultural”) and sees stagnation, and in many clear cases decline. He looks at general population health, life expectancy (including uprooting some fond assumptions about our ancestors), marriage, children, economic mobility, wealth vs education and a host of other factors. I won’t bring the detail here but it’s worth your time, even if it’s a bit of a depressing read: more depressing if you’re young:

When it turns to the economics that effects all of those things, the main target is declining productivity. There’s a fair bit of argument about how to measure that:

In The Great Stagnation, Tyler Cowen suggested that the conventional productivity measures may be misleading. For example, he noted that productivity growth through 2000–2004 averaged 3.8 percent, a very high figure and an outlier relative to most of the last half-century.

…

The United States still leads the way in innovation…But the development of productivity-enhancing new technologies has been slower over the past few decades than in any comparable span of time since the beginning of the Industrial Revolution in the early 18th century…The social technologies of recent years facilitate consumption rather than production.As a result, growth in total factor productivity has been slow for a long time.

…

“What we measured as value creation actually may have been value destruction, namely too many homes and too much financial innovation of the wrong kind.” Then, productivity shot up by over 5 percent in 2009–2010, but Cohen found that it was mostly the result of firms firing the least productive people. That may have been good business, but it’s not the same as productivity rising because innovation is reducing scarcity and thus leading to better living standards.

And the decline shows up in other ways also, with the economy becoming more financialised, which means that resources are increasingly channeled into means of extracting wealth from the productive economy instead of producing goods and services, which leads to crazy stuff like the following:

General Electric, the manufacturing giant founded by Thomas Edison, transformed itself into a black box of finance businesses, dragging itself down as a result. The total market value of major airlines like American, United, and Delta is less than the value of their loyalty programs, in which people get miles by flying and by spending with airline-branded credit cards.

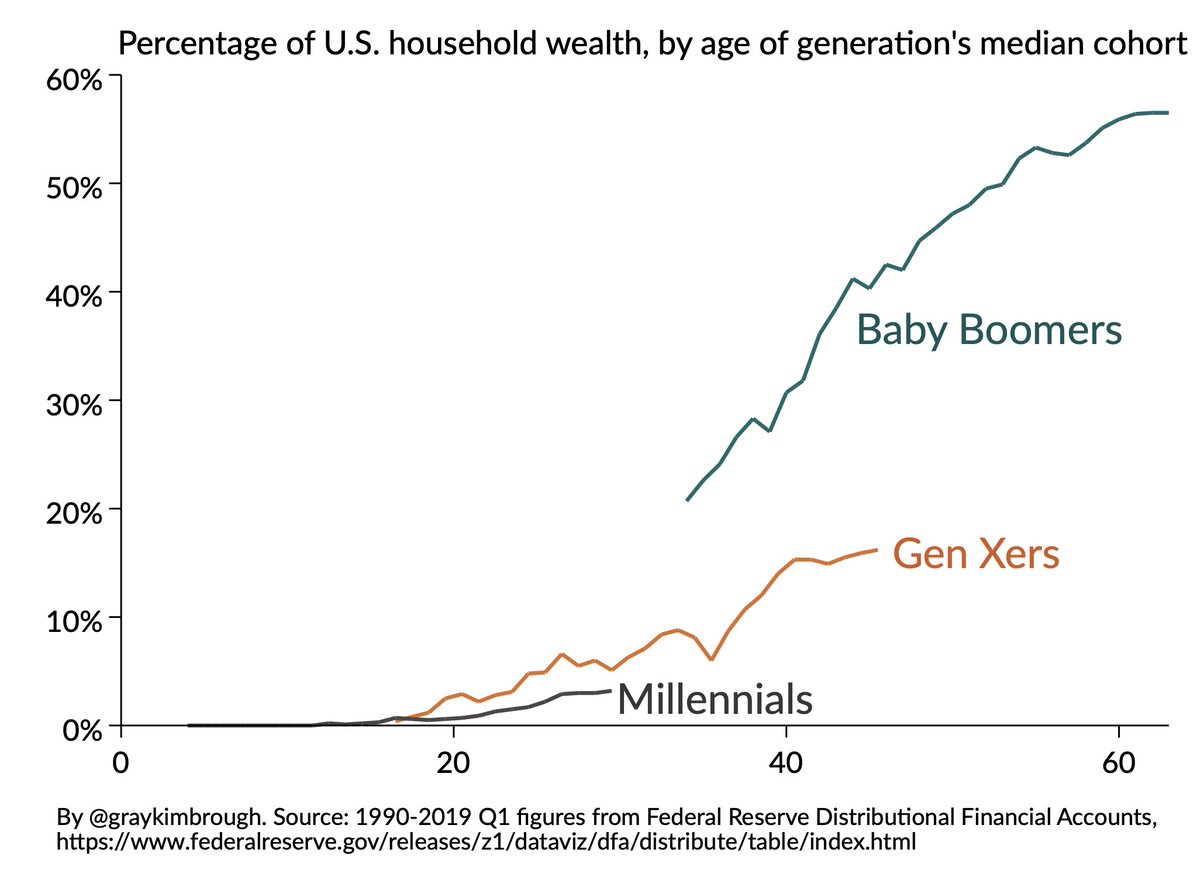

Economically I understand how this works. But it’s still crazy and I don’t think it’s good for society in the long run, especially if you don’t own assets (see the Millennials above). This is the “Cantillon effect“, and the article explains the awful way in which it works, including student debt and the two-income family as need rather than choice.

The last article finishes by pointing out the same thing the first article did, as well as Zimmerman and Eisenhower; invention has to be enabled by a culture that is willing to allow disruptive ideas to be heard and even implemented on a small scale, and what we’ve got now increasingly does the opposite, aided too often by government funding and control.

I guess its long wave economic theory of development.?

Our society has been advancing for 500- 600 years, starting in the Renaiisance, and accelerating with the industrial revolution.

The counter revolution has begun and will no doubt hold sway for a 100 odd years, several generations at least.

There will then be a paradigm shift, and mankind will leap forward again. Possibly spurred what the excitement of space, and what its frontiers has to offer. As well as the acceptance of nuclear as the energy of the future which will free man once more.

You can see this clearly in Wellington now. Big Government, Marxists and socialist dressed up as Greens, preaching bicycles and demonising cars and progress. They are a cabal much like the Catholic church of the Middle Ages.

Capitalism has been captured by big finance. There is no added value in that, just making bond and money dealers, like John Key super rich, without advancing civilisation.

Sorry, its like most things, civilisation does not advance on a straight line, its a wavy curve around a mid point and that curve is heading south at the moment.

Call back in about 200 years!

I’m not sure your examples of inventors are that good…. e.g. edison vs tesla, the latter exhibited behavior much closer to your description. I agree that the science paradigm has lost the ‘take nobody’s word for it’ ethos of the royal society and were published results sadly align with the sources of funding, like the MSM.

test